& meet dozens of singles today!

User blogs

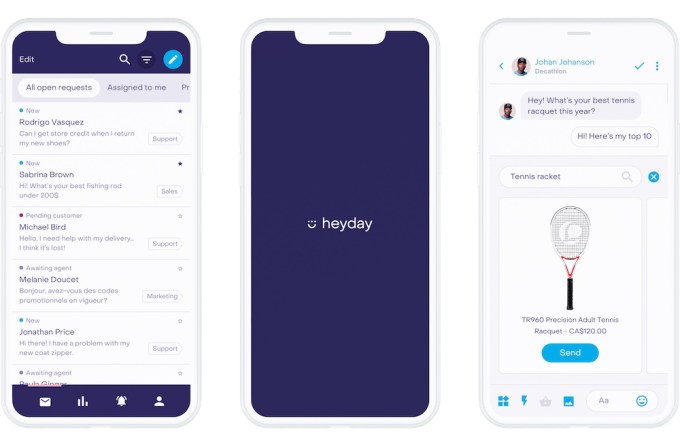

Montreal-based Heyday announced today that it has raised $6.5 million Canadian ($5.1 million in US dollars) in additional seed funding.

Co-founder and CEO Steve Desjarlais told me that the startup’s goal is to allow retailers to support more automation and more personalization in their online customer interactions, while co-founder and CMO Etienne Merineau described it as an “all-in-one unified customer messaging platform.”

So whether a customer is sending a message from Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and Google’s Business Messages or just via email, Heyday brings all that communication together in one dashboard. It then uses artificial intelligence to determine whether it’s a customer service or sales-related interaction, and it automates basic responses when possible.

Heyday chatbots can provide order updates or even recommend products (it integrates with Salesforce, Shopify, Magento, Lightspeed and PrestaShop), then route the conversation to a human team member when necessary.

There are other platforms that combine customer service and sales, but at the same time, Merineau said it’s important to treat the two categories as distinct and trust that a good service experience will lead to sales in the feature.

Image Credits: Heyday

“We believe that helping is the new selling,” he said.

Desjarlais added, “We’re really against the ticket ID system. A customer is not a ticket …

I truly believe that every single customer is a relationship with a brand that needs to be nurtured over time and that will give more value to the brand over time.”

Heyday was founded in 2017 and says that over the past two quarters, it has doubled recurring revenue. Customers include French sporting good company Decathlon, Danish fashion house Bestseller to food and consumer product brand Dannon — Merineau noted that the platform was “bilingual out of the box” and has seen strong international growth.

“Retailers who believe that [the changes brought about by] COVID-19 are temporary are in the wrong mindset,” he said. “The new mantra of future-forward brands is ‘adapt or die.’ … Brands obviously want to delvier great service, but they care about the bottom line. We help them kill two birds with one stone.”

The startup had previously raised $2 million Canadian, according to Crunchbase. This new round comes from existing investors Innovobot and Desjardins Capital. Merineau said the money will help Heyday “double down on the U.S. and scale.”

The U.S. Department of Defense is setting up a working group to focus on climate change.

The new group will be led by Joe Bryan, who was appointed as a Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense focused on climate earlier this year.

The move is one of several steps that the Biden administration has taken to push an agenda that looks to address the dangers posed by global climate change.

Bryan, who previously served as Deputy Assistant to the Secretary of the Navy for Energy under the Obama administration, will oversee a group intended to coordinate the Department’s responses to Biden’s recent executive order and subsequent climate and energy-related directives and track implementation of climate and energy-related actions and progress, according to a statement.

The Department of Defense controls the purse strings for hundreds of billions of dollars in government spending and is a huge consumer of electricity, oil and gas, and industrial materials. Any steps it takes to improve the efficiency of its supply chain, reduce the emissions profile of its fleet of vehicles, and use renewable energy to power operations could make a huge contribution to the commercialization of renewable and sustainable technologies and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

The Pentagon is already including security implications of climate change in its risk analyses, strategy development and planning guidance, according to the statement, and is including those risk analyses in its intallation planning, modeling, simulation and war gaming, and the National Defense Strategy.

“Whether it is increasing platform efficiency to improve freedom of action in contested logistics environments, or deploying new energy solutions to strengthen resilience of key capabilities at installations, our mission objectives are well aligned with our climate goals,” wrote Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, in a statement. “The Department will leverage that alignment to modernize the force, strengthen our supply chains, identify opportunities to work closely with allies and partners, and compete with China for the energy technologies that are essential to our future success.”

Facebook has challenged the FTC’s antitrust case against it using a standard playbook that questions the agency’s arguably expansive approach to defining monopolies. But the old arguments of “we’re not a monopoly because we never raised prices” and “how can it be anticompetitive if we never allowed competition” may soon be challenged by new doctrine and the new administration.

In a document filed today which you can read at the bottom of this post, Facebook lays out its case with a tone of aggrieved pathos:

By a one-vote margin, in the fraught environment of relentless criticism of Facebook for matters entirely unrelated to antitrust concerns, the agency decided to bring a case against Facebook that ignores its own prior decisions, controlling precedent, and the limits of its statutory authority.

Yes, Facebook is the victim here, and don’t you forget it. (Incidentally, the FTC, like the FCC, is designed to split 3:2 along party lines, so the “one vote margin” is what one sees for many important measures.)

But after the requisite crying comes the reluctant explanation that the FTC doesn’t know its own business. The suit against Facebook, the company argues, should be spiked by the judge because it fails along three lines.

First, the FTC does not “allege a plausible relevant market.” After all, to have a monopoly, one must have a market over which to exert that monopoly. And the FTC, Facebook argues, has not done so, alleging only a nebulous “personal social networking” market, and “no court has ever held that such a free goods market exists for antitrust purposes,” and the FTC ignores the “relentlessly competitive” advertising market that actually makes the company money.

Ultimately, the FTC’s efforts to structure a crabbed ‘use’ market for a free service in which it can claim a large Facebook ‘share’ are artificial and incoherent.

The implication here is not just that the FTC has failed to define the social media market (and Facebook won’t do so itself), but that such a market may not even exist because social media is free and the money is made by a different market. This is a variation on a standard big tech argument that amounts to “because we do not fall under any of the existing categories, we are effectively unregulated.” After all you cannot regulate a social media company by its advertising practices or vice versa (though they may be intertwined in some ways, they are distinct businesses in others).

Thusly Facebook attempts, like many before it, to squeeze between the cracks in the regulatory framework.

This continues with the second argument, which says that the FTC “cannot establish that Facebook has increased prices or restricted output because the agency acknowledges that Facebook’s products are offered for free and in unlimited quantities.”

The argument is literally that if the product is free to the consumer, it is by definition not possible for the provider to have a monopoly. When the FTC argues that Facebook controls 60 percent of the social media market (which of course doesn’t exist anyway), what does that even mean? 60 percent of zero dollars, or 100 percent, or 20 percent, is still zero.

The third argument is that the behaviors the FTC singles out — purchasing up-and-coming competitors for enormous sums and nipping others in the bud by restricting its own platform and data — are not only perfectly legal but that the agency has no standing to challenge them, having given its blessing before and having no specific illegal activity to point to at present.

Of course the FTC revisits mergers and acquisitions all the time, and there’s precedent for unraveling them long afterwards if, for instance, new information comes to light that was not available during the review process.

“Facebook acquired a small photo-sharing service in 2012, Instagram… after that acquisition was reviewed and cleared by the FTC in a unanimous 5-0 vote,” the company argues. Leaving aside the absurd characterization of the billion-dollar purchase as “small,” leaks and disclosures of internal conversations contemporary with the acquisition have cast it in a completely new light. Facebook, then far less secure than it is today, was spooked and worried that Instagram may eat its lunch, and it was better to buy than compete.

The FTC addresses this and indeed many of the other points Facebook raises in a FAQ it posted around the time of the original filing.

Now, some of these arguments may have seemed a little strange to you. Why should it matter if a market has money from consumers being exchanged if there is value exchanged elsewhere contingent on those users’ engagement with the service, for instance? And how can the depredations of a company in the context of a free product that invades privacy (and has faced enormous fines for doing so) be judged by its actions in an adjacent market, like advertising?

The simple truth is that antitrust law has been stuck in a rut for decades, weighed down by doctrine that states that markets are defined by the price of a product and whether a company can increase it arbitrarily. A steel manufacturer that absorbs its competitors by undercutting them and then later raises prices when it is the only option is a simple example and the type that antitrust laws were created to combat.

If that seems needlessly simplistic, well, it’s more complicated in practice and has been effective in many circumstances — but the last 30 years have shown it to be inadequate to address the more complex multi-business domains of the likes of Microsoft, Google, and Facebook (to say nothing of TechCrunch parent company Verizon, which is a whole other matter).

The ascendance of Amazon is one of the best examples of the failure of antitrust doctrine, and resulted in a breakthrough paper called “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox” which pilloried these outdated ideas and showed how network effects led to subtler but no less effective anticompetitive practices. Establishment voices decried it as naive and overreaching, and progressive voices lauded it as the next wave of antitrust philosophy.

It seems that the latter camp may win out, as the author of this controversial paper, Lina Khan, has just been nominated for the vacant 5th Commissioner position at the FTC.

Whether or not she is confirmed (she will face fierce opposition, no doubt, as an outsider plainly opposed to the status quo), her nomination validates her view as an important one. With Khan and her allies in charge at the FTC and elsewhere, the decades-old assumptions that Facebook relies on for its pro forma rejection of the FTC lawsuit may be challenged.

That may not matter for the present lawsuit, which is unlikely to be subject to said rules given its rather retrospective character, but the gloves will be off for the next round — and make no mistake, there will be a next round.

Federal Trade Commission v Facebook Inc Dcdce-20-03590 0056.1 by TechCrunch on Scribd

Twitter says it’s running a test with a small subset of iOS and Android users to “give people an accurate preview” of what an image will look like without the trial and error that process involves now. As it stands now, the platform automatically crops images to make them display in a more condensed way in the timeline, where users often scroll through without clicking on an image preview. But that approach has created some problems.

Today we’re launching a test to a small group on iOS and Android to give people an accurate preview of how their images will appear when they Tweet a photo. pic.twitter.com/cxu7wv3Khs

— Dantley Davis (@dantley) March 10, 2021

The biggest one, historically, is that Twitter’s algorithm that decides which part of an image gets the focus was demonstrated to have baked-in racial bias. The algorithm prioritized white faces over Black ones in its image preview, even cropping out the former president of the United States in one person’s tests.

Twitter’s automatic image handling is also hassle for photographers and artists, who generally prefer to have total control over how an image is presented. If the crop is off, that small misfire can be the difference between a photo attracting a ton of attention or getting ignored outright. It also ruins narrative tweets, as Twitter notes in its example of the tweet about a dog who is conspicuously absent from one of its crops.

It sounds like Twitter is also trying out showing more full images in the timeline. In tweets, Twitter’s Chief Design Officer Dantley Davis said that anyone testing the new image cropping system will find that most single image tweets in normal aspect ratios won’t get a crop at all, though super wide or super tall images will get a crop weighted around the center.

For photographers (present company included) tired of toggling between Instagram’s preference for portrait-oriented images and Twitter’s insistence on landscape crops, that’s good news too. As you can see in the sample image, the change could actually make Twitter a richer visual platform. That would likely mean more scrolling past images that take up multiple tweets worth of vertical space, but we’d be happy to trade the time spent clicking through images for a prettier Twitter timeline.