& meet dozens of singles today!

User blogs

Everybody says they want to build user-centric companies and products, but how exactly is that achieved? Talking and listening to users, of course — a task that is both unnecessarily time-consuming and cumbersome to organise, according to Axel Thomson, a former product manager at U.K. recipe-box subscription unicorn Gousto.

His burgeoning startup, dubbed Ribbon, wants to make it easy for product teams to recruit and interview users, and to “continuously test and validate their hypotheses”. This, it’s hoped, will then lead to better products for users. The idea was born out of a need Thomson says he experienced himself while leading a user experience-focused product team at Gousto.

“I initially joined Gousto in the growth team, running product and marketing experiments focused on improving the user experience and increasing retention before moving over to the product team to work on improving the user experience more holistically,” he tells me.

“In both of these teams we had to constantly make decisions on what features and experiments we wanted to take bets on, quickly realising that as much as we thought we knew what the users wanted, the best way to find out was by having real conversations with users, and letting them test out different concepts. This was a big eye-opener to how difficult it could be to consistently make good and informed decisions on which products and features were worth testing and which ones were doomed to fail”.

Thomson says it’s become a trope within management circles that product teams should be user-centric and that products should be designed to help users solve “real problems”. But in reality, it’s often hard to know what users really think or actually want, while continuously doing user research and conducting interviews is very time-consuming.

“Teams will often spend days setting up interviews, resulting in a slow feedback loop that slows down product development and experimentation,” he says. “Alternatively, product teams seek solace in quantitative data from analytics platforms such as Amplitude and Mixpanel, which only give insight into how users have used their products once they’ve been shipped”.

Enter Ribbon, which its founder says lets companies start user interviews in roughly “the same time it takes to order a ride through Uber”. Product teams simply install the Ribbon widget on their website and can then recruit and conduct video interviews with users any point in the user journey.

“We want to help product teams rapidly and continuously do user interviews, and ultimately any type of qualitative user research, without having to make compromises on how quickly they can ship, how reliable results they can get and how frequently they can do research,” explains Thomson.

Ribbon is designed to appeal to product managers, designers and user researchers, all of whom benefit from validating their ideas by having conversations with users. However, Thomson argues that the benefits of user research isn’t limited to these roles only, and that while companies often have dedicated teams or people that “own” user interviews, there is an increasing interest in “socialising research findings and participation in user research across companies”.

“Our goal as a user research platform is to make it easy for our users to become evangelists of their research within their own teams and organisations, by making it really easy to do great research and share it with your team,” he adds.

It’s still early days, of course — Ribbon launched its MVP to the Product Hunt community at the end of October last year. Until now, the London-based startup has been bootstrapped, too, but today is disclosing that it has raised £200,000 in pre-seed funding from MMC Ventures, RLC Ventures and a group of London-based angels.

Meniga, the London fintech that provides digital banking technology to leading banks, has closed €10 million in additional funding.

The round is led by Velocity Capital and Frumtak Ventures. Also participating are Industrifonden, the U.K. Government’s Future Fund and existing customers UniCredit, Swedbank, Groupe BPCE and Íslandsbanki.

Meniga says the funding will be used for continued investment in R&D, and in particular further development of green banking products — building on its carbon spending insights product. In addition, the fintech will bolster its sales and service teams.

Headquartered in London but with additional offices in Reykjavik, Stockholm, Warsaw, Singapore and Barcelona, Meniga’s digital banking solutions help banks (and other fintechs) use personal finance data to innovate in their online and mobile offerings.

Its various products include a software layer that bridges the gap between a bank’s legacy tech infrastructure and a modern API, making it easier to build consumer-friendly digital banking experiences. The product suite spans data aggregation technologies, personal and business finance management solutions, cash-back rewards and transaction-based carbon insights.

Meniga tells TechCrunch it has experienced a significant increase in the demand for its digital banking products and services over the past year. This has seen the fintech launch a total of 18 digital banking solutions across 17 countries.

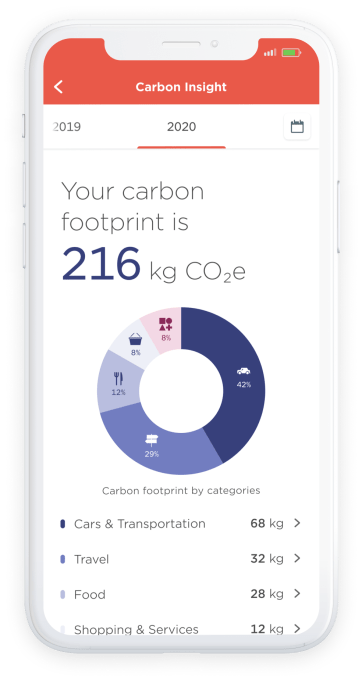

Image Credits: Meniga

Helping fuel that demand is the need for banks to attract and retain a generation of customers that increasingly care about sustainability and the need to tackle climate change. Enter Meniga’s green banking solution: Dubbed “Carbon Insight,” it leverages personal finance data so that mobile banking customers can track and, in theory, reduce their carbon footprint.

Specifically, it lets users track their estimated carbon footprint for a given time period (which can be broken down into specific spending categories); track the estimated carbon footprint of individual transactions; and compare their overall carbon footprint and the carbon footprint of spending categories with that of other users.

Last month, Íslandsbanki became the first Nordic bank to implement Meniga’s Carbon Insight solution into its own digital banking offering.

Outlets that follow the crypto industry have been observing a trend, which is that according to Google search data, the rise in interest in non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, now almost matches the level of interest in 2017 in initial coin offerings, or ICOs.

Of course, ICOs largely disappeared from the scene after the SEC started poking around and determining, in some cases, that they were being used to launder money. Now experts in blockchain transactions see the potential for abuse again with NFTs, despite the traceable nature of the tokens — and perhaps even because of it.

As most readers may know at this point (because they’re increasingly hard to avoid), an NFT is a kind of digital collectible that can come in almost any form, a PDF, a tweet — even a digitized New York Times column.

Each of these items — and there can be many copies of the same item — is stamped with a long string of alphanumerics that makes it immutable. As early crypto investor David Pakman of Venrock explains it, that code is also recorded on the blockchain, so that there’s a permanent record of who own what. Someone else can screenshot that PDF or tweet or Times column, but they won’t be able to do anything with that screenshot, whereas the NFT owner can, theoretically at least, sell that collectible at some point to a higher bidder.

The biggest NFT sale to date, about 15 days ago, was the sale of digital artist Mike Winkelmann’s “Everydays: The First 5000 Days,” which sold for a stunning $69 million — the third-highest auction price achieved for a living artist, after Jeff Koons and David Hockney. Winkelmann, who uses the name Beeple, broke his own record with the sale, having sold another crypto art piece for $6.6 million in February. (Earlier this week, he sold yet another for $6 million.) There is such a frenzy that Beeple has told numerous outlets that he believes there’s a crypto art “bubble” and that many NFTs will “absolutely go to zero.”

There is so much money involved that experts believe that NFTs have become a rife opportunity for bad actors, even if action hasn’t been brought against one yet.

One of the most practical dangers centers on trade-based money laundering, or the process of disguising illegal proceeds by moving them through trade transactions in an effort to legitimize them. It’s already a huge issue in the art world, and NFTs are comparable to art, with even more erratic pricing right now.

Jesse Spiro, the chief of government affairs at the blockchain analysis firm Chainalysis explains it this way: “One of the ways to identify trade-based money laundering with [traditional] art is that [an appraiser] comes up with a fair market value for something, and you’re able to measure that fair market value against the pricing that’s involved [and flag] over invoicing or under invoicing, which is either selling that asset for less than it’s worth, or for more than it’s worth.”

The good news is that in some instances where hundreds or even thousands of NFTs are being sold, even at very different prices, as has been happening with NBA highlight clips, there’s an average value that can be measured, Spiro notes, and that makes unusual activity easier to spot.

In cases where it’s impossible to establish a sales history, however, its ultimate price “could be whatever the buyer is willing to pay for something, so you can’t really make that determination” that something nefarious is afoot. According to Spiro, “All that’s needed is two parties that are involved to effectively execute that [transaction] successfully.”

There are many other flavors of crime when it comes to digital assets and, potentially, with regard to NFTs. Asaf Meir, the cofounder and CEO of the crypto market surveillance company Solidus Labs, points as examples to wash trades, where an individual or outfit simultaneously sells and buys the same financial instruments; as well as cross trades, which involve a trade between two accounts within the same organization, all to create a false record around the price of an asset that doesn’t reflect the true market price.

Both are illegal under money laundering laws and also very hard to spot, especially for legacy systems. The “tricky thing about the crypto markets is they are retail-oriented first, so there could be multiple different accounts with multiple addresses doing multiple things in collusion — sometimes mixed or not mixed with institutional accounts for different beneficial owners,” says Meir, who met his cofounders at Goldman Sachs, where they worked on the electronic trading desk for equities and quickly observed that surveillance for digital assets was very much an unsolved issue.

It’s worth noting that not everyone thinks it likely that NFTs are being used to transfer money illegally. Says Pakman, an investor in the NFT marketplace Dapper Labs, “Crytpo purists are upset this happened, but national governments can go to marketplaces and exchanges and they can say, ‘In order for you to do business, you need to follow [know-your-customer] and [anti-money-laundering] laws that force [these entities] to get a verified identify of everyone of their customers. Then any suspicious transactions over a certain amount, they have to file paperwork.”

The two tools make it easier for authorities to subpoena the marketplaces and exchanges when a suspicious transaction is flagged and force the outfits to verify their user’s identity.

Still, one question is how effective such a process is if enough time elapses between the suspicious transaction and it being flagged. Pakman answers that “everything is retroactively researchable. If you get away with it today, there’s nothing to stop the FBI from tracking it a year later.”

Another question is why money launderers would bother with NFTs when there are easier ways to transfer large sums of money in the crypto world. Max Galka, cofounder and CEO of the blockchain analytics platform Elementus, says that “one piece that kind of makes me think NFTs might not be the best vehicle for money laundering is just that secondary markets are not as liquid,” meaning it isn’t so easy for bad actors to create distance between themselves and a transaction.

Galka also wonders whether a criminal wouldn’t instead simply go to a decentralized exchange and buy up liquid tokens that are truly fungible (meaning no unique information can be written into the token) so that the location of those funds is harder to trace than with a nonfungible token.

“I certainly see the potential for money laundering here, but given that there are lots of assets out there on the blockchain that people can use for that, [NFTs] may not be best-suited” compared with their other options, says Galka.

Theoretically, Spiro of Chainalysis agrees on all fronts, but he suggests that the minting and sale of NFTs have ballooned so fast that a lot of processes that should be in place are not.

“Most NFTs operate on the Ethereum blockchain, so it’s technically true that these are traceable,” he says. It’s also true that “the entities running these NFTs should have compliance and work with blockchain forensics and analytics to ensure that someone is able to follow the flow of funds.”

Indeed, he says, in an “ideal world, you’d be able to follow transactions, and then at the choke points where individuals were trying to convert whatever token they’re using into maybe fiat currency, they’d have to provide their [personal identifiable information]” and law enforcement or regulators could then see if the transaction was connected to illicit activity.

We’re not there yet, though, which means bad things could very definitely be happening.

“Right now,” says Spiro, “compliance in relation to these NFTs is a gray area.”

Hong Kong-based viAct helps construction sites perform around-the-clock monitoring with an AI-based cloud platform that combines computer vision, edge devices and a mobile app. The startup announced today it has raised a $2 million seed round, co-led by SOSV and Vectr Ventures. The funding included participation from Alibaba Hong Kong Entrepreneurs Fund, Artesian Ventures and ParticleX.

Founded in 2016, viAct currently serves more than 30 construction industry clients in Asia and Europe. Its new funding will be used on research and development, product development and expanding into Southeast Asian countries.

The platform uses computer vision to detect potential safety hazards, construction progress and the location of machinery and materials. Real-time alerts are sent to a mobile app with a simple interface, designed for engineers who are often “working in a noisy and dynamic environment that makes it hard to look at detailed dashboards,” co-founder and chief operating officer Hugo Cheuk told TechCrunch.

As companies signed up for viAct to monitor sites while complying with COVID-19 social distancing measures, the company provided training over Zoom to help teams onboard more quickly.

Cheuk said the company’s initial markets in Southeast Asia will include Indonesia and Vietnam because government planning for smart cities and new infrastructure means new construction projects there will increase over the next five to 10 years. It will also enter Singapore because developers are willing to adopt AI-based technology.

In a press statement, SOSV partner and Chinaccelerator managing director Oscar Ramos said, “COVID has accelerated digital transformation and traditional industries like construction are going through an even faster process of transformation that is critical for survival. The viAct team has not only created a product that drives value for the industry but has also been able to earn the trust of their customers and accelerate adoption.”