& meet dozens of singles today!

User blogs

“Headless commerce” is a phrase that gets thrown around lot (I’ve typed it several times today already), but Vue Storefront CEO Patrick Friday has an especially vivid way of using the concept to illustrate his startup’s place in the broader ecosystem.

“Vue Storefront is the bodiless front-end,” Friday said. “We are the walking head.”

In other words, while most headless commerce companies are focused on creating back-end infrastructure, Vue powers the front-end, namely the progressive web applications with which consumers actually interact. The company describes itself as “the lightning-fast frontend platform for headless commerce.”

Friday said that he and CTO Filip Rakowski created the Vue Storefront technology as an open-source project while working at e-commerce agency Divante, before eventually spinning it out into a separate startup last year. The company was also part of the most recent class at accelerator Y Combinator, and it recently raised $1.5 million in seed funding led by SMOK Ventures and Movens VC.

“We had to set up a new entity in the middle of COVID, we had to raise in the middle of COVID and we had to convince the agency get rid of the product in the middle of COVID,” Friday said. He even recalled signing papers with an investor one morning in early December and doing an interview with Y Combinator that evening.

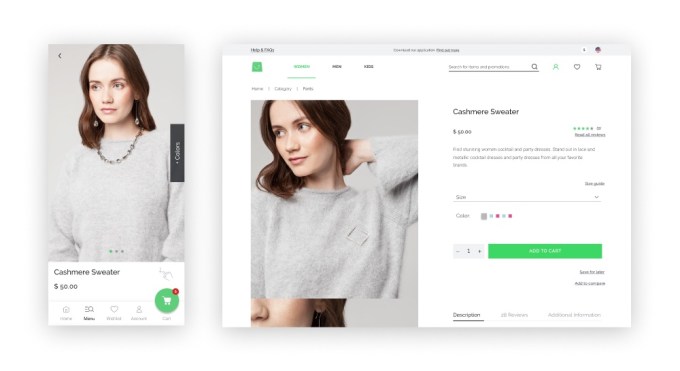

Image Credits: Vue Storefront

As they’ve built a business around the core open-source technology, Friday and his team have realized that Vue has more to offer than just building web apps, because it connects e-commerce platforms like Magento and Shopify with headless content management systems like Contentstack and Contentful, payments systems like PayPal and Stripe and other third-party services.

In fact, Friday said customers have been telling them, “You are like the glue. Headless was so complex to me, and then I got this Vue Storefront thing to come in on top everything else and be the glue connecting things.”

The platform has been used to create more than 300 stores worldwide. Friday said adoption has accelerated as the pandemic and resulting growth in e-commerce have driven businesses to realize they’re using “this legacy platform, using outdated frameworks and technologies from a good four or five years ago.”

Rakowski added, “We also see that many customers actually come to us deciding that Vue Storefront can be the first step of migration to another platform. We can quickly migrate the front-end and write back-end agnostic code.”

Because it had just raised funding, the Vue Storefront team did not participant in the recent YC Demo Day, and will be presenting at the next Demo Day instead. In the meantime, it will be holding its own virtual Vue Storefront Summit on April 20.

This year is all about the roll-ups. No, not those fruity snacks you used to find in your lunchbox; roll-ups are the aggregation of smaller companies into larger firms, creating a potentially compelling path for equity value.

Right now, all eyes are on Thrasio, the fastest company to reach unicorn status, and its cadre of competitors, such as Heyday, Branded and Perch, all vying to become the modern model of consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies.

Making things even more interesting, famed investor and operator Keith Rabois recently announced that he too is working on a roll-up concept called OpenStore with Atomic co-founder Jack Abraham.

Like any investment firm, to be successful, a roll-up should have a thesis or two providing it with a cohesive strategy across its portfolio.

Thrasio has been reaping the benefits of the e-commerce market’s Cambrian explosion in 2020, in which over $1 billion of capital was invested in firms on a mission to acquire independent Amazon sellers and brands.

This catalyst can be attributed to a few key factors, the first and most notable being the pandemic accelerating spending on Amazon and e-commerce more broadly. Next is the low cost of capital, a reflection of interest rates making markets flush with cash; this has made it easier to raise both equity and debt capital.

The third is the emerging and quantifiable proofs of concept: Thrasio is one of several raising hundreds of millions of dollars, and Anker, a primarily Amazon-native brand, went public. Both stories have provided further validation that a meaningful brand can be built on top of Amazon’s marketplace.

Still, the interest in creating value through e-commerce brands is particularly striking. Just a year ago, digitally native brands had fallen out of favor with venture capitalists after so many failed to create venture-scale returns. So what’s the roll-up hype about?

Roll-ups are another flavor of investing

Roll-ups aren’t a new concept; they’ve existed for a while. In the offline world, roll-ups often achieve much greater exit multiples, known as “multiple arbitrage,” so it’s no surprise that the trend is making its way online.

Historically, though, roll-ups haven’t been all that successful; HBR notes that more than two-thirds of roll-ups fail to create value for investors. While roll-ups are often effective at building larger companies, they don’t always increase profits or operating cash flows.

Acquirers, i.e., those rolling up smaller companies, need to uncover new operating approaches for their acquired companies to increase equity value, and the only way to increase equity value is to increase operating cash flow. There are four ways to do this: reducing overhead costs, reducing operating costs without sacrificing price or volume, increasing pricing without sacrificing volume or increasing volume without increasing unit costs.

E-commerce could present a new and different opportunity, or at least that’s what investors and smart money are betting on. Let’s explore how this new wave of roll-ups is approaching both growth and value creation.

Channel your enthusiasm: Why every roll-up needs a thesis

Like any investment firm, to be successful, a roll-up should have a thesis or two providing it with a cohesive strategy across its portfolio. There are a few that are trending in this particular wave.

The first is the primary distribution channel upon which a company grows. Evaluating companies with a common distribution channel can be helpful for creating economies of scale, focusing marketing and growth resources in a specific channel versus diluting resources across several.

On the downside, these companies become reliant on this distribution strategy and any changes could create vulnerabilities for their portfolio companies. As a study, let’s take a look at how two companies take different approaches:

This week’s Amazon public relations push will no doubt go down as one of the odder public-facing strategies in tech. As some of the company’s biggest rivals were getting ready to virtually testify on Capitol Hill, the retail giant’s CEO of worldwide consumer business appeared to suggest that Amazon is not only as progressive as self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, but also more effective in achieving those leftist policies.

Ahead of the Vermont senator’s visit to Amazon’s Bessemer, Alabama fulfillment center, Dave Clark tweeted, “I welcome [Sanders] to Birmingham and appreciate his push for a progressive workplace. I often say we are the Bernie Sanders of employers, but that’s not quite right because we actually deliver a progressive workplace.”

1/3 I welcome @SenSanders to Birmingham and appreciate his push for a progressive workplace. I often say we are the Bernie Sanders of employers, but that’s not quite right because we actually deliver a progressive workplace https://t.co/Fq8D6vyuh9

— Dave Clark (@davehclark) March 24, 2021

The statement was unsurprisingly greeted with pushback from labor groups. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) sent TechCrunch a lengthy response from president Stuart Appelbaum to the odd statement:

How arrogant and tone deaf can Amazon be? Do they really believe that the wage they pay – which is below what workers in nearby unionized warehouses receive and below Alabama’s median wage – gives them the right to mistreat and dehumanize their employees, put their workers’ health and safety in jeopardy, require them to maintain an unbearable pace, which even Amazon itself admits that a quarter of their workforce won’t be able to meet, and to deny working men and women the dignity and respect they deserve.

The organization, which is helping facilitate the Bessemer warehouse’s union voting, goes on to cite high turnover rates and pay cuts amid the pandemic and founder Jeff Bezos’s ballooning wealth. The founder — who is set to step down as CEO some time in Q3 — reportedly added more than $72 billion to his net worth in 2020, as Amazon employees became essential workers amid COVID-19-fueled shutdowns.

For many in the U.S., Amazon’s online delivery service provided a lifeline, as many stores were forced to close over pandemic precautions. The Bessemer facility opened on March 29, just as the first wave was cresting in the U.S. The company was anticipating a potential strain on its resources as record numbers of Americans were suddenly forced to stay home and were otherwise avoiding in-person shopping at all costs.

“Our team at Amazon is thankful for the support we have received from state and community leaders, and we are excited to be a part of the Bessemer community,” Director of Operations Travis Maynard said at the time. “We’re proud to create great jobs in Bessemer with industry-leading pay and benefits that start on day one, in a safe, innovative workplace.”

After several years of negative coverage over its warehouse working conditions, it’s not surprising that the company has become proactively reflexive when it comes to working conditions.

“When New York City became the epicenter [of COVID-19], that’s when the Bessemer facility opened up,” Christian Smalls, a former Amazon worker-turned-critic said at TechCrunch’s Justice event earlier this month. “So the union got a head start on talking to workers. So that’s a gem for anybody or any union that plans on trying to unionize the building — that you have a facility in your community that’s about to open up, when opening, that’s the best time to connect with workers. That’s what happened last year. And as a result, the workers had seen what happened to the workers that were unprotected and they don’t want that. They want better for themselves.”

Next week, the RWDSU will begin tallying votes for what has shaped up to be the largest union push since Amazon’s 1995 founding, much to the company’s chagrin. In recent months, the company has been hoping to throw a wrench in the works. In January, it unsuccessfully appealed a ruling by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that allowed workers to vote by mail, as more than 350,000 COVID-19 cases had been reported in the state since the beginning of the pandemic.

Amazon expressed concerns that mail-in voting would monopolize too much time and resources. “Union avoidance” firm Jackson Lewis suggested that such rules put employers at a disadvantage, “because eligible voters are given several days after receiving their ballots to return them to the NLRB, the impact and momentum of the employer’s voter education campaign is decreased. This does not exist in connection with a manual ballot election, where the employer may educate employees one-on-one until the last moment before they vote.”

NEW: Amazon is running glossy anti-union ads to combat the organizing drive by workers at their Bessemer, AL, warehouse. An Alabama resident said this spot is one of several that Amazon is now running on Twitch. pic.twitter.com/6WlojetvzY

— More Perfect Union (@MorePerfectUS) February 23, 2021

The following month, Amazon ran anti-union ads on its streaming subsidiary, Twitch. The spots featured employees discussing why they were planning to vote no, and compelled people to visit Do it Without Dues, which blasted potential union membership fees.

“Amazon feels that it has to go to extremes like this in order to gaslight its workers about the dreadful working conditions at its Bessemer warehouse,” Appelbaum told the press in response to the ads. Twitch pulled the spots, adding that they, “should never have been allowed to run on [the] service.”

BIRMINGHAM, AL – MARCH 05: A truck passes as Congressional delegates visit the Amazon Fulfillment Center after meeting with workers and organizers involved in the Amazon BHM1 facility unionization effort, represented by the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union on March 5, 2021 in Birmingham, Alabama. Workers at Amazon facility currently make $15 an hour, however they feel that their requests for less strict work mandates are not being heard by management. (Photo by Megan Varner/Getty Images)

Workers have continued to be critical of conditions in Amazon’s warehouses, frequently comparing the work to that of robots that have increasingly become their colleagues. Last week, New York Magazine published a piece from a Bessemer picker who describes long and tiring days on the floor.

“It really is not fair for employees to get fired for going to the bathroom,” the worker, Darryl Richardson, tells the magazine. “Sometimes the water in the bathrooms isn’t working on the floor, and you have to go down another flight of stairs to go to the bathroom.”

A number of similar stories have been recounted to the media over the years. Images of workers peeing in water bottles so as to not be docked pay — or worse — for taking a bathroom break have almost certainly become the most visceral.

1/2 You don’t really believe the peeing in bottles thing, do you? If that were true, nobody would work for us. The truth is that we have over a million incredible employees around the world who are proud of what they do, and have great wages and health care from day one.

— Amazon News (@amazonnews) March 25, 2021

When Wisconsin Rep. Mark Pocan called out Clark’s Sanders comparisons on Twitter earlier this week, an official account shot back, “We hope you can enact policies that get other employers to offer what we already do.”

Sanders has been a long-time critic of the company. The Vermont senator was one of a handful of progressive politicians who compelled Amazon to raise its minimum wage to $15 an hour, while criticizing massive tax breaks. In 2018, he introduced the Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies (BEZOS) bill.

“The taxpayers in this country should not be subsidizing a guy who’s worth $150 billion, whose wealth is increasing by $260 million every single day,” Sanders told TechCrunch at the time. “That is insane. He has enough money to pay his workers a living wage. He does not need corporate welfare. And our goal is to see that Bezos pays his workers a living wage.” That November, the company relented, increasing minimum wage to $15 an hour — something that has since become a major talking point for Amazon.

Responding to Pocan’s comments about “union-bust[ing] & mak[ing] workers urinate in water bottles,” the Amazon News Twitter account wrote, “You don’t really believe the peeing in bottles thing, do you? If that were true, nobody would work for us. The truth is that we have over a million incredible employees around the world who are proud of what they do, and have great wages and health care from day one.”

And yes, I do believe your workers.

You don't?

— Rep. Mark Pocan (@repmarkpocan) March 25, 2021

Pocan’s reply was simple: “[Y]es, I do believe your workers. You don’t?”

In addition to past reports of warehouse workers and delivery drivers peeing in bottles, a new report from The Intercept notes that the act is “widespread,” due to workplace pressures. It cites an email from last May that also adds defecation into the mix.

“We’ve noticed an uptick recently of all kinds of unsanitary garbage being left inside bags: used masks, gloves, bottles of urine,” the email titled Amazon Confidential reads. “By scanning the QR code on the bag, we can easily identify the DA who was in possession of the bag last. These behaviors are unacceptable, and will result in Tier 1 Infractions going forward. Please communicate this message to your drivers. I know it may seem obvious, or like something you shouldn’t need to coach, but please be explicit when communicating the message that they CANNOT poop, or leave bottles of urine inside bags.”

Pro-union demonstration signs during a Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) held protest outside the Amazon.com Inc. BHM1 Fulfillment Center in Bessemer, Alabama, U.S., on Sunday, Feb. 7, 2021. The campaign in Bessemer to unionize Amazon workers has drawn national attention and is widely considered a once-in-a-generation opportunity to breach the defenses of the worlds largest online retailer, which has managed to keep unions out of its U.S. operations for a quarter-century. Photographer: Elijah Nouvelage/Bloomberg via Getty Images

As misguided or glib as the Amazon Twitter response may seem, it’s clear why the company has gone on the offensive here. “We’re not alone in our support for a higher federal minimum wage,” the accounted noted in the wake of the dustup with Pocan. The company adds that it has been pushing for a federal minimum wage increase following its own.

The push to unionize, meanwhile, has made strange political bedfellows, ranging from Stacey Abrams to Marco Rubio. Breaking with the customary party position, the Republican senator wrote in an op-ed, “Here’s my standard: When the conflict is between working Americans and a company whose leadership has decided to wage culture war against working-class values, the choice is easy — I support the workers. And that’s why I stand with those at Amazon’s Bessemer warehouse today.”

Rubio’s support of unionizing was tied, in part, to concerns over a “‘woke’ human resources fad,” but it’s still fairly uncommon for an event like this to find him on the side of the likes of Joe Biden, who had previously promised to be “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen.”

Amazon will no doubt be keeping a close eye on Tuesday’s vote count, aware that the results will have a far wider ranging impact than the 6,000 workers currently employed at Bessemer. If unionization fails, the company will tout the results as vindication that its work force is perfectly happily without labor interference. A vote to unionize, on the other hand, could well embolden further unionization efforts across the company.

While new headless commerce platforms are emerging all the time, Swell CEO Eric Ingram told me that it remains “really hard to do something new in e-commerce.”

Specifically, he told me that most headless platforms (which offer back-end infrastructure separate from the front-end shopping experience) allow businesses to build a faster shopping experience, but they’re largely designed for marketplaces where you search, browse and purchase from a traditional product catalog.

“The most interesting ideas in e-commerce aren’t just another catalog,” Ingram said.

Swell, which is announcing that it has raised $3.4 million in seed funding, was designed to offer more flexibility when it comes to the underlying business models. Ingram (who founded the company with Stefan Kende, Dave Loneragan, Joshua Voydik and Mark Regal) described it as the “future-proof backend” for e-commerce companies, which can grow and adapt with them as their business models evolve.

“Typical catalogs” have been built on the platform, he said, but it also supports Spinn‘s marketplace of independent coffee roasters, B2B vacuum pump marketplace Nowvac and ethical direct-to-consumer diamond retailer Great Heights.

In fact, Voydik described Swell as “infinitely flexible.” Among other things, the company says it achieves this flexibility by offering API access to every component, as well as native subscription support and an unlimited number of product attributes.

“Every store on Swell effectively has their own database SaaS platform,” Ingram added.

Overall, he said the platform offers the flexibility that you’d normally get from an open source approach without the technical headaches: “No one wants to maintain their own code base and their own database.”

He continued, “You don’t need to be technical, you don’t need to have developers to leverage this. A lot of our customers are developers, but a lot of them are just regular marketers and ops people who know a bit of development concepts and want to have control over the systems.”

The startup’s new funding was led Jim Andelman of Bonfire Ventures, with participation from Willow Growth Partners, Andreas Klinger of Remote First Capital, Vercel CEO Guillermo Rauch, GitHub CTO Jason Warner and former Salesforce Commerce Cloud CTO Mike Micucci.

Robotic process automation platform UiPath added its name to the list of companies pursuing public-market offerings this morning with the release of its S-1 filing. The document details a quickly growing software company with sharply improving profitability performance. The company also flipped from cash burn to cash generation on both an operating and free-cash-flow basis in its most recent fiscal year.

Companies that produce robotic process automation (RPA) software help enterprises reduce labor costs and errors. Instead of having a human perform repetitive tasks like data entry, processing credit card applications and scheduling cable installation appointments, RPA tools employ software bots instead.

The phrase that matters most when digesting this IPO filing is operating leverage, what Investopedia defines as “the degree to which a firm or project can increase operating income by increasing revenue.” In simpler terms, we can think of operating leverage as how quickly a company can boost profitability by growing its revenue.

The greater a company’s operating leverage, the more profitable it becomes as it grows its top line; in contrast, companies that see their profitability profile erode as their revenue scales have poor operating leverage.

Among early-stage companies in growth mode, losing money is not a sin — after all, startups raise capital to deploy it, often making their near-term financial results a bit wonky from a traditionalist perspective. But for later-stage companies, the ability to demonstrate operating leverage is a great way to indicate future profitability, or at least future cash-flow generation.

So, the UiPath S-1 filing is at once an interesting picture of a company growing quickly while reducing its deficits rapidly, and a look at what a high-growth company can do to show investors that it will, at some point, generate unadjusted net income.

There are caveats, however: UiPath had some particular cost declines in its most recent fiscal year that make its profitability picture a bit rosier than it otherwise might have proven, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. This morning, now that we’ve looked at the big numbers, let’s dig in a bit deeper and learn whether UiPath is as strong in operating leverage terms as a casual observer of its filing might guess.

And then we’ll dig into four other things that stuck out from its IPO filing. Into the data!

Operating leverage, cost control and COVID-19

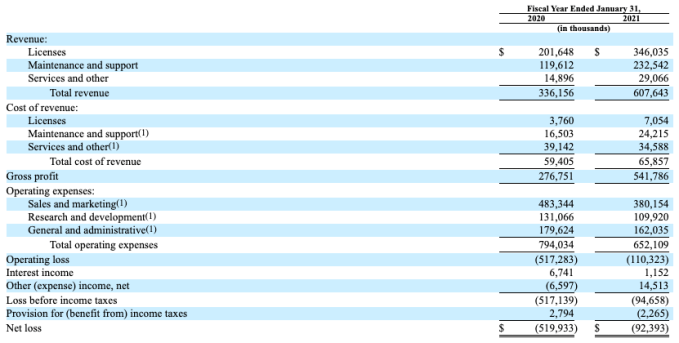

To avoid forcing you to flip between the filing and this piece, here’s UiPath’s income statement for its fiscal years that roughly correlate to calendar 2019 and calendar 2020:

From top-down, it’s clear UiPath is growing rapidly. And we can see that its gross profit grew more quickly than its overall revenue in its most recent 12-month period. As you can imagine, that combination led to rising gross margins at the company, from 82% in its fiscal year ending January 31, 2020, to 89% in its next fiscal year.

That’s super good, frankly; given that UiPath has a number of business lines, including a services effort that doubled in size during its most recent 12 months of operations, you might expect its blended gross margins to fade. They did not.

But it’s the following section, the company’s cost profile, that leads us to our first real takeaway from the UiPath S-1:

UiPath’s operating leverage looks good, even if COVID helped

Every operating expense category at the company fell from the preceding fiscal year to its most recent. That’s an impressive result, and one that is key when it comes to understanding where UiPath’s recent operating leverage came from. But how the declines came to be is just as important to understand.