& meet dozens of singles today!

User blogs

Hipmunk’s founders are building a successor to their now-defunct flight search service.

The startup was acquired by SAP-owned travel and expense platform Concur in 2016, and its CEO Adam Goldstein departed in 2018. But Goldstein told me he and his co-founder Steve Huffman (also co-founder and CEO of Reddit) were still disappointed when Concur shut the service down at the beginning of last year.

“Over the years, there were millions and millions of people who used it and loved it,” Goldstein said. (I was one of those people — even before I knew what he was working on, I started out our call by telling Goldstein how much I miss Hipmunk.)

So the pair seed funded a project called Flight Penguin, with Goldstein serving as the new company’s chairman. And he said the actual product was built by former Hipmunk developer Sheri Zada.

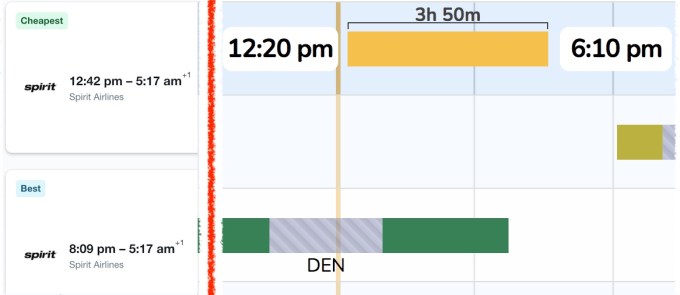

The Flight Penguin interface will be very familiar to old Hipmunk users, with a visual layout that makes it easy to see the timing of flights and length of layovers. And just as Hipmunk allowed users to organize results by “agony” (so that the top results aren’t just cheap flights with inconvenient timing or ridiculous layovers), Flight Penguin allows them to sort their flights by “pain.”

Image Credits: Flight Penguin

But this isn’t just the old experience with a fresh coat of paint — it’s also meant to improve on Hipmunk in a few key ways. For one thing, it allows users to search by Chase Ultimate Rewards Points (as well as U.S. dollars, with the goal of adding more currencies and rewards programs in the future).

And the product itself is a Google Chrome extension, rather than a traditional flight search website. The extension actually presents a full, standalone web experience (rather than an overlay on another website), but Goldstein said this approach is still important, because it allows Flight Penguin to pull its data “through the frontend instead of the backend,” giving it the most up-to-date data. This helps to avoid situations where a flight or price shows up in search results but isn’t available on the airline’s or other seller’s website.

In addition, Goldstein said Flight Penguin will show “all the flights.” In other words, it won’t be making any deals with the airlines to hide certain flights or prices, and it will also show airlines that don’t normally make their flights available on other search platforms.

“There are actually many, many flights available but consumers don’t see them because travel search sites work out these deals,” he said. “We’re choosing not to play that game.”

That has the obvious benefit of offering more comprehensive results, but also the disadvantage that Flight Penguin will not be able to collect affiliate fees for flight purchases. Instead, after a 30-day trial period, it will charge users $10 per month. (This is an introductory fee and will likely change in the future.)

Goldstein acknowledged that this is probably “not going to be a mainstream product that 50 million Americans use,” but he’s hoping that it can attract a significant subscriber base of frequent travelers who “value their time and care about the flight booking experience.”

“What we learned from Hipmunk was […] the way business has traditionally been done in online travel worked for consumer in an era lots of competition between airlines and travel agencies,” he added. “In a world where there’s much less competition, you’re basically becoming an agent for the people you’re working with, and i’s hard to build a business model around providing a great user experience. That’s why we’re saying that we’re going to opt out of this game and play by our own rules.”

Flight Penguin is currently accepting signups for its waitlist, but Goldstein said the company is simply using this to bring users on in a controlled fashion, and that it plans to move people off the wait list pretty quickly.

Clubhouse, a one-year-old social audio app reportedly valued at $1 billion, will now allow users to send money to their favorite creators — or speakers — on the platform. In a blog post, the startup announced the new monetization feature, Clubhouse Payments, as the “the first of many features that allow creators to get paid directly on Clubhouse.”

Clubhouse’s press team did not immediately respond to comment. Paul Davison, the co-founder of Clubhouse, mentioned in the company’s latest town hall that the startup wants to focus on direct monetization on creators, instead of advertisements.

Here’s how it will work: A user can send a payment in Clubhouse by going to the profile of the creator to whom they want to give money. If the creator has the feature enabled, the user will be able to tap “Send Money” and enter an amount. It’s like a virtual tip jar, or a Clubhouse-branded version of Venmo (although the payments feature doesn’t currently let the user send a personalized message along with the money).

.@joinClubhouse

@stripe pic.twitter.com/u7kXXdPXU7

— edwin (@edwinwee) April 5, 2021

“100% of the payment will go to the creator. The person sending the money will also be charged a small card processing fee, which will go directly to our payment processing partner, Stripe,” the post reads. “Clubhouse will take nothing.”

Stripe CEO Patrick Collison tweeted shortly after the blog post went up that “It’s cool to see a new social platform focus first on participant income rather than internalized monetization / advertising.”

It's cool to see a new social platform focus first on *participant* income rather than internalized monetization / advertising. Excited for the burgeoning creator economy and next era of internet business models.

— Patrick Collison (@patrickc) April 5, 2021

When the startup raised a Series B led by Andreessen Horowitz in January, part of the reported $100 million funding was said to go to a creator grant program. The program would be used to “support emerging Clubhouse creators,” according to a blog post. It’s unclear how they define emerging, but cultivating influencers (and rewarding them with money) is one way the startup is promoting high-quality content on its platform.

The synergies here are obvious. A Clubhouse creator can now get tips for a great show, or raise money for a great cause, while also being rewarded by the platform itself for being a recurring host.

The fact that Clubhouse’s first attempt at monetization includes no percentage cut of its own is certainly noteworthy. Monetization, or Clubhouse’s lack thereof, has been a topic of discussion about the buzzy startup since it took off in the early pandemic months. While it currently relies on venture capital to keep the wheels churning, it will need to make money eventually in order to be a self-sustaining business.

Creator monetization, with a cut for the platform, has led to the growth of large businesses. Cameo, a startup that sends personalized messages from creators and celebrities, takes about a 25% cut of each video sold on its platform. The startup reached unicorn status last week with a $100 million raise. OnlyFans, another platform that helps creators directly raise money from fans in exchange for paywalled contact, is projecting $1 billion in revenue for 2021.

Clubhouse’s payments feature will first be tested by a “small test group” starting today, but it is unclear who is in this group. Eventually, the payments feature will be rolled out to other users in waves.

For those who follow the space, LG will be remembered fondly as a smartphone trailblazer. For a decade-and-a-half, the company was a major player in the Android category and a driving force behind a number of innovations that have since become standard.

Perhaps the most notable story is that of the LG Prada. Announced a month before the first iPhone, the device helped pioneer the touchscreen form factor that has come to define virtually every smartphone since. At the time, the company openly accused Apple of ripping off its design, noting, “We consider that Apple copycat Prada phone after the design was unveiled when it was presented in the iF Design Award and won the prize in September 2006.”

LG has continued pushing envelopes – albeit to mixed effect. In the end, however, the company just couldn’t keep up. This week, the South Korean electronics giant announced it will be getting out of the “incredibly competitive” category, choosing instead to focus on its myriad other departments.

The news comes as little surprise following months of rumors that the company was actively looking for a buyer for the smartphone unit. In the end, it seems, none were forthcoming. This July, the company will stop selling phones beyond what remains of its existing inventory.

The smartphone category is, indeed, a competitive one. And frankly, LG’s numbers have pretty consistently fallen into the “Others” category of global smartphone market share figures ruled by names like Samsung, Apple, Huawei and Xiaomi. The other names clustered beneath the top five have been, more often than not, other Chinese manufacturers like Vivo.

Apple CEO Tim Cook dropped a few hints in an interview released Monday about the direction of the much-anticipated Apple car, including that autonomous vehicle technology will likely be a key feature.

“The autonomy itself is a core technology, in my view,” Cook told Kara Swisher in an interview on the “Sway” podcast. “If you sort of step back, the car, in a lot of ways, is a robot. An autonomous car is a robot. And so there’s lots of things you can do with autonomy. And we’ll see what Apple does.”

Cook was careful not to reveal too much, declining to answer Swisher’s question outright if Apple is planning to produce a car itself or the tech within the car. What clues he did drop, suggests Project Titan is working on something in the middle.

“We love to integrate hardware, software and services, and find the intersection points of those because we think that’s where the magic occurs,” said Cook. “And we love to own the primary technology that’s around that.”

To which Swisher responded: “I’m going to go with car for that, if you don’t mind. I’m just going to jump to car.”

We are, too.

Many people in the micromobility industry like to say that e-scooters are basically iPhones on wheels, but it’s more likely that the Apple car will actually be the iPhone on wheels. Apple is generally known for owning all of its hardware and software, so it wouldn’t be surprising to see Apple engineers working closely with a manufacturer to produce an Apple car, with the potential to one day cut out the middle man and become the manufacturer.

The so-called Project Titan appeared at risk of failing before a car was ever seen by the public with mass layoffs in 2019. However, more recent reports suggest that the project is alive and well with plans to make a self-driving electric passenger vehicle by 2024.

Earlier this year, CNBC reported that Apple was close to finalizing a deal with Hyundai-Kia to build an Apple-branded self-driving car at the Kia assembly plant in West Point, Georgia. Sources familiar with Apple’s interest in Hyundai say the company wants to work with an automaker that will let Apple hold the reins on the software and hardware that will go into the car.

The two companies never reached a deal and talks fell apart in February, according to multiple reports. That hasn’t stopped the flow of rumors and reports about Apple and its plans, which have previously been linked to other suppliers, automakers such as Nissan and even startups.

It’s still unclear what the Apple car will look like, but as a passenger vehicle, rather than a robotaxi or delivery vehicle, it will be going up against the likes of Tesla.

“I’ve never spoken to Elon, although I have great admiration and respect for the company he’s built,” said Cook. “I think Tesla has done an unbelievable job of not only establishing the lead, but keeping the lead for such a long period of time in the EV space. So I have great appreciation for them.”

Project Titan is being led by Doug Field, who was formerly senior vice president of engineering at Tesla and one of the key players behind the Model 3 launch.

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas flaunted a dangerous ignorance regarding matters digital in an opinion published today. In attempting to explain the legal difficulties of social media platforms, particularly those arising from Twitter’s ban of Trump, he makes an ill-informed, bordering on bizarre, argument as to why such companies may need their First Amendment rights curtailed.

There are several points on which Thomas seems to willfully misconstrue or misunderstand the issues.

The first is in his characterization of Trump’s use of Twitter. You may remember that several people sued after being blocked by Trump, alleging that his use of the platform amounted to creating a “public forum” in a legal sense, meaning it was unlawful to exclude anyone from it for political reasons. (The case, as it happens, was rendered moot after its appeal and dismissed by the court except as a Thomas’s temporary soapbox.)

“But Mr. Trump, it turned out, had only limited control of the account; Twitter has permanently removed the account from the platform,” writes Thomas. “[I]t seems rather odd to say something is a government forum when a private company has unrestricted authority to do away with it.”

Does it? Does it seem odd? Because a few paragraphs later, he uses the example of a government agency using a conference room in a hotel to hold a public hearing. They can’t kick people out for voicing their political opinions, certainly, because the room is a de facto public forum. But if someone is loud and disruptive, they can ask hotel security to remove that person, because the room is de jure a privately owned space.

Yet the obvious third example, and the one clearly most relevant to the situation at hand, is skipped. What if it is the government representatives who are being loud and disruptive, to the point where the hotel must make the choice whether to remove them?

It says something that this scenario, so remarkably close a metaphor for what actually happened, is not considered. Perhaps it casts the ostensibly “odd” situation and actors in too clear a light, for Thomas’s other arguments suggest he is not for clarity here but for muddying the waters ahead of a partisan knife fight over free speech.

In his best “I’m not saying, I’m just saying” tone, Thomas presents his reasoning why, if the problem is that these platforms have too much power over free speech, then historically there just happen to be some legal options to limit that power.

Thomas argues first, and worst, that platforms like Facebook and Google may amount to “common carriers,” a term that goes back centuries to actual carriers of cargo, but which is now a common legal concept that refers to services that act as simple distribution – “bound to serve all customers alike, without discrimination.” A telephone company is the most common example, in that it cannot and does not choose what connections it makes, nor what conversations happen over those connections – it moves electric signals from one phone to another.

But as he notes at the outset of his commentary, “applying old doctrines to new digital platforms is rarely straightforward.” And Thomas’s method of doing so is spurious.

“Though digital instead of physical, they are at bottom communications networks, and they ‘carry’ information from one user to another,” he says, and equates telephone companies laying cable with companies like Google laying “information infrastructure that can be controlled in much the same way.”

Now, this is certainly wrong. So wrong in so many ways that it’s hard to know where to start and when to stop.

The idea that companies like Facebook and Google are equivalent to telephone lines is such a reach that it seems almost like a joke. These are companies that have built entire business empires by adding enormous amounts of storage, processing, analysis, and other services on top of the element of pure communication. One might as easily suggest that because computers are just a simple piece of hardware that moves data around, that Apple is a common carrier as well. It’s really not so far a logical leap!

There’s no real need to get into the technical and legal reasons why this opinion is wrong, however, because these grounds have been covered so extensively over the years, particularly by the FCC — which the Supreme Court has deferred to as an expert agency on this matter. If Facebook were a common carrier (or telecommunications service), it would fall under the FCC’s jurisdiction — but it doesn’t, because it isn’t, and really, no one thinks it is. This has been supported over and over, by multiple FCCs and administrations, and the deferral is itself a Supreme Court precedent that has become doctrine.

In fact, and this is really the cherry on top, freshman Justice Kavanaugh in a truly stupefying legal opinion a few years ago argued so far in the other direction that it became wrong in a totally different way! It was Kavanaugh’s considered opinion that the bar for qualifying as a common carrier was actually so high that even broadband providers don’t qualify for it (This was all in service of taking down net neutrality, a saga we are in danger of resuming soon). As his erudite colleague Judge Srinivasan explained to him at the time, this approach too is embarrassingly wrong.

Looking at these two opinions, of two sitting conservative Supreme Court Justices, you may find the arguments strangely at odds, yet they are wrong after a common fashion.

Kavanaugh claims that broadband providers, the plainest form of digital common carrier conceivable, are in fact providing all kinds sophisticated services over and above their functionality as a pipe (they aren’t). Thomas claims that companies actually providing all kinds of sophisticated services are nothing more than pipes.

Simply stated, these men have no regard for the facts but have chosen the definition that best suits their political purposes: for Kavanaugh, thwarting a Democrat-led push for strong net neutrality rules; for Thomas, asserting control over social media companies perceived as having an anti-conservative bias.

The case Thomas uses for his sounding board on these topics was rightly rendered moot — Trump is no longer president and the account no longer exists — but he makes it clear that he regrets this extremely.

“As Twitter made clear, the right to cut off speech lies most powerfully in the hands of private digital platforms,” he concludes. “The extent to which that power matters for purposes of the First Amendment and the extent to which that power could lawfully be modified raise interesting and important questions. This petition, unfortunately, affords us no opportunity to confront them.”

Between the common carrier argument and questioning the form of Section 230 (of which in this article), Thomas’s hypotheticals break the seals on several legal avenues to restrict First Amendment rights of digital platforms, as well as legitimizing those (largely on one side of the political spectrum) who claim a grievance along these lines. (Slate legal commentator Mark Joseph Stern, who spotted the opinion early, goes further, calling Thomas’s argument a “paranoid Marxist delusion” and providing some other interesting context.)

This is not to say that social media and tech do not deserve scrutiny on any number of fronts — they exist in an alarming global vacuum of regulatory powers, and hardly anyone would suggest they have been entirely responsible with this freedom. But the arguments of Thomas and Kavanaugh stink of cynical partisan sophistry. This endorsement by Thomas amounts accomplishes nothing legally, but will provide valuable fuel for the bitter fires of contention — though they hardly needed it.